How Bekaert Transformed 75 Plants, and Why Most DX Efforts Fail

Welcome to DX Brief - Manufacturing, where every week, we interview practitioners and distill industry podcasts and conferences into what you need to know

In today's issue:

How Bekaert transformed 75 factories by anchoring every decision on business value

Why change management must precede technology selection, not follow it

Building a modern industrial tech-stack across 27 sites

1. How Bekaert transformed 75 factories by anchoring every decision on business value

CIONET podcast, Episode: Embracing Digital Transformation with Gunter Van Craen - CDIO at Bekaert (Dec. 4, 2025)

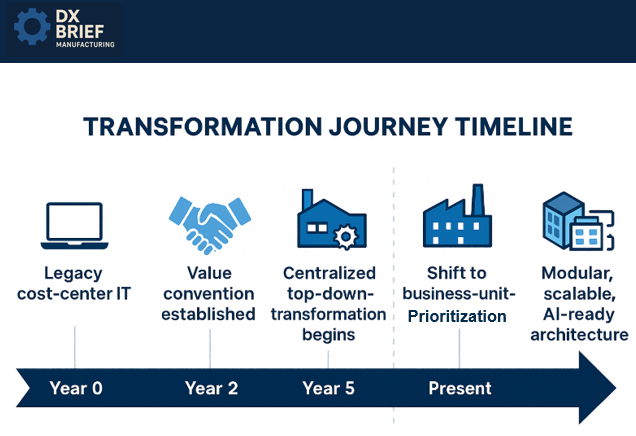

Background: Gunter Van Craen took a 100-year-old Belgian steel wire manufacturer from a cost-center IT function to a modern, scalable digital operation spanning 75 factories across 21,000 employees. But the real insight isn't the technology stack. It's how he created a "value convention" with the executive committee that eliminated the endless debates about whether digital investments actually show up in the P&L. Here's the framework for transforming industrial companies where "we're not Nike" is the default objection.

TLDR:

Agree on a value convention with your executive team before launching transformation. When everyone speaks the same language about how value is defined and measured, ROI debates disappear.

Use a top-down approach to get started, then deliberately pivot to bottom-up after demonstrating results. Bekaert ran centralized transformation for 3 years before shifting to business-unit-driven prioritization.

Build modular architecture designed for reuse from day one. Bekaert reduced project costs from 500K to 100K by scaling pre-built capabilities across business units with only four manufacturing templates.

Start with value language, not technology language. Van Craen's first move wasn't implementing systems. It was spending three months getting the executive committee to agree on what "value realized" actually means.

Most transformation leaders skip this step and pay for it forever. Every function comes to the board claiming value creation, but business unit leaders roll their eyes because nothing shows up in their P&L.

Use top-down to ignite, bottom-up to sustain. Van Craen acknowledges his top-down approach generates "disagreements with some of my peers." But for an organization that laughed him out of the room when he first mentioned customer-centric thinking, waiting for consensus meant waiting forever.

He pushed transformation down for three years, then deliberately transitioned. Now quarterly reviews with each business unit drive prioritization. Now, business units are asking for more than he can deliver, not resisting what's being imposed.

Architect for reuse obsessively. With 75 plants and multiple business units, complexity could have killed the program. Van Craen simplified by identifying just four manufacturing templates (make-to-order, project business, etc.) and building architecture fit for each. The result: what once cost 500K per implementation now costs 100K. "Cost is not really the pivotal conversation anymore."

Create AI-readiness as a byproduct. Van Craen didn't anticipate AI's acceleration five years ago. But by building a proper data architecture focused on structured data they "understand, curate, and trust," Bekaert now has an asset ready for AI deployment. The transformation created future optionality.

What to do about this:

→ Schedule a value convention session with your executive committee. Block 2-3 hours to explicitly define what "value realized" means for your transformation. Get sign-off before any new initiative.

→ Audit your architecture for reuse. Map manufacturing processes to a small number of templates. Ask: How many of our digital capabilities could scale to other plants or business units with minimal modification?

→ Plan your top-down-to-bottom-up transition. If you're early in transformation, set a 2-3 year milestone where you'll shift from centralized pushing to business-unit-driven pulling.

2. Why change management must precede technology selection, not follow it

Manufacturers Make Strides podcast, Episode: A people-first digital transformation with Ryan Pollyniak (Dec. 2, 2025)

Background: Ryan Pollyniak has spent 15 years guiding manufacturers through ERP transformations. "Technology is only part of the equation... willingness and desire to change on the personal level is what differentiates success and failure." The root cause of projects failing is almost never the software.

TLDR:

Don't tell your team "we're changing whether you like it or not." That works for motivation but kills desire. Motivation gets compliance, desire gets adoption.

Prep your team for change before you even select a product. Projects that introduce users to the system at UAT (user acceptance testing) are already too late.

Temporarily backfill day-jobs during transformation, not the project team. Your best people need to drive the change, not squeeze it between existing responsibilities.

Motivation is not desire. Pollyniak uses the ADCAR change management framework to make a crucial distinction. "You're motivated to change if you're going to lose your job... But do you actually want to change?" He uses the seatbelt analogy: "Click it or ticket" motivates rule-followers. "Save your life" motivates the self-preservation crowd. Both achieve compliance, but through different paths to desire. Manufacturing transformations fail when leaders assume mandate equals adoption.

Start change management before vendor selection. The most common failure pattern: "Their people haven't seen the system until UAT... It's far too late at that point." Change management isn't a project phase. It's the foundation that must be laid before you pick technology: "Here's the journey we're going on. Here's why we're going on it. We'll let you know as we select partners and products."

The house-building analogy. "You wouldn't go to a home builder and say, 'Build me a three-bedroom house with a two-car garage.' The builder can do it, right? But is it going to have the tile you want?" Handing transformation to IT alone produces the equivalent of a house with random finishes. Business process owners must document requirements before technical teams engage vendors.

Backfill the day-job, not the project. Here's counterintuitive advice: "I do not recommend temporarily staffing an ERP project. Temporarily backfill the day-to-day lives of the people who are critical to your organization and free their time up to be part of a project." Your best operators need to drive the transformation. Their expertise and credibility make adoption stick.

The gym membership problem. "Who's ever gone and worked out for a couple days in the gym and next thing you know 6 months later you haven't touched it?" Without sustained reinforcement – accountability partners, KPI-linked incentives, public recognition – people revert to whiteboards and Excel sheets. Human nature defeats technology investment.

What to do about this:

→ Build a motivation-to-desire bridge for each role. Map your key transformation stakeholders. For each, identify: What's their motivation? What would create genuine desire? How do we bridge the gap?

→ Launch change communication before vendor evaluation. Draft your "here's the journey" message now, even if you haven't selected technology. Get leadership aligned on the narrative before you engage vendors.

→ Plan your backfill strategy. Identify the 3-5 people who must be on your transformation team. Then plan how to cover their current responsibilities—don't expect them to do both.

→ Design your "workout buddy" system. What will sustain adoption after go-live? Peer accountability? Manager check-ins? KPI-linked bonuses?

3. Building a modern industrial tech-stack across 27 sites

Wrench Factor podcast, Episode: IT-Ops Divide: How to Build a Modern Industrial Tech Stack with Blaine Bryant – CIO at Lightera (Dec. 2, 2025)

Background: "There are two types of businesses in the world: those that are technology companies, and those that haven't recognized that they're technology companies yet." Blaine Bryant is driving global IT consolidation, MES standardization, data modernization, and cybersecurity maturity across 27 manufacturing sites that came from 3 different companies with wildly different technology maturity levels. His framework for IT-OT convergence starts with the insight that the technologies won't converge by themselves. You need architects, not just engineers, and relationships before roadmaps.

TLDR:

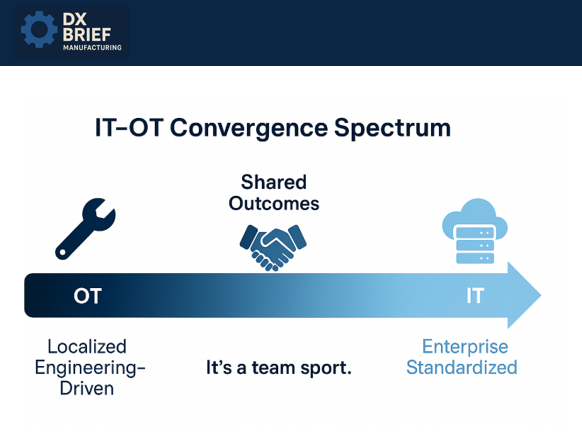

IT and OT are incentivized differently, which creates natural friction. Operations solves localized problems; IT drives enterprise standardization. Acknowledge this tension and build bridges through relationships and shared outcomes, not mandates.

Create a cross-functional steering committee that owns both IT and OT obsolescence risk at the enterprise level. Local plant managers often defer technical debt under budget pressure, creating hidden enterprise-level risk.

Be "standardized to the extent that makes sense but also adaptable to what's truly required to be unique." When you bring this message authentically, the people closest to the work often respond with "Hallelujah, we've been waiting for this."

IT-OT tension stems from how these organizations are born, bred, and incentivized. OT tends to be very aligned with manufacturing operations and process engineering. They're focused on specific challenges that are often very localized.

IT has requirements from a global perspective to bring modernization, standardization, and efficiency for the enterprise. Those worlds don't always meet with the greatest collaboration and consistency.

The solution isn't to force alignment. It's to recognize that everyone wants the same outcomes: the highest quality product, greatest efficiency, best on-time delivery, and optimal operating income.

"Why should we want to help the other? IT can't achieve the outcomes the enterprise expects by itself. OT can't do it by itself. We have to recognize it's a team sport."

Bring architects to the table, not just engineers. "IT organizations and particularly OT organizations are steeped with engineers that want to solve problems.

But the enlightened organization will bring to bear some architects that ask:

Can we take this to other locations?

Can we standardize to a greater extent?

Can we engage in volume discount negotiations with strategic suppliers?

These questions transform local wins into enterprise value. "People are running around with technical solutions looking for a business problem," Bryant observes. "Instead of the other way around."

Create enterprise visibility into OT obsolescence risk. In most organizations, OT obsolescence risk is managed locally. Each plant manager has their "top 10 list" of upgrades they'd make with the next half million in capex.

But under budget pressure, that risk gets deferred. The can gets kicked down the road. "If you do that long enough, you compound your risk at a particular location."

The solution: a steering committee that assesses IT and OT obsolescence risk in the same pass, using a common template for data collection.

The process identifies the top 10 at each location, then rolls up to an enterprise top 10. "What are the biggest operational risks to this company that could potentially threaten achievement of financial targets?"

This enterprise-level visibility – common in IT and cybersecurity – is often missing in OT.

Be standardized where it matters, adaptable where it's required. Bryant anticipates the pushback: "You hear that and you say, 'Sounds like a heavy corporate-driven thing pushed out to the plants.' And you get some resistance."

"What we want to do is be standardized to the extent that makes sense but also be adaptable to what's truly required to be unique at a particular location."

This requires listening, participation, and healthy dialogue between localities, regions, leadership levels, and IT/OT disciplines.

The payoff? "What we found is the people closest to the work are kind of like, 'Hallelujah. We've been waiting for this.' This makes total sense."

The resistance typically comes from middle management layers "looking through the wrong end of the telescope and kind of overfocused on the short-term cost as opposed to the long-term efficiency and effectiveness."

What to do about this:

→ Establish an IT-OT steering committee with enterprise-level risk visibility. Create a common template for assessing both IT and OT obsolescence risk. Roll up local top-10 lists into an enterprise top-10. Make technical debt visible to leadership accountable for enterprise risk.

→ Add architects to your engineering-heavy teams. Before implementing solutions to local problems, ask: Does this scale? Can we take it to other locations? Can we leverage volume pricing with strategic suppliers? The extra architectural rigor transforms point solutions into platform capabilities.

Disclaimer

This newsletter is for informational purposes only and summarizes public sources and podcast discussions at a high level. It is not legal, financial, tax, security, or implementation advice, and it does not endorse any product, vendor, or approach. Manufacturing environments, laws, and technologies change quickly; details may be incomplete or out of date. Always validate requirements, security, data protection, labor, and accessibility implications for your organization, and consult qualified advisors before making decisions or changes. All trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners.